Fruitful Collaborations: Libraries as Partners in Historical Research

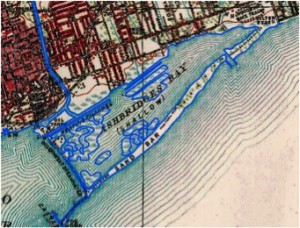

Part of my doctoral research on the social and environmental history of Toronto’s Don River Valley involved making sense of the area’s industrial past. Given the volatile nature of nineteenth-century industry—some companies opening and closing again in short succession, others changing hands, and names, numerous times over the space of a few decades—this proved more challenging than I had imagined. I found myself on the fourth floor of the Toronto Reference Library, photocopying unwieldy fire insurance plans and taping them together, however imperfectly, to create a giant visual mosaic of building outlines along the lower river. Tiled together, each paper collage stretched the full height of my office walls; each represented just one year in the history of the river. Surely, I thought, there had to be an easier way of doing this. But we historians are no strangers to tedium and frustration, most of us having logged considerable hours in front of microfilm readers and in archives of varying states of organization. I resolved to continue my efforts with tape and photocopier.

It wasn’t until some months later that an unrelated email exchange with University of Toronto Map and GIS librarian Marcel Fortin led to a conversation about the nature of my research, and the difficulties I was experiencing in interpreting the spatial history of the area. My timing was fortunate: Marcel saw the potential of using my project as test case to showcase both the rich resources of the university library’s map collection and the dramatic interpretive and presentation capabilities of GIS.

Support from a NiCHE project grant allowed us to hire a research assistant to begin the work of scanning and georeferencing historical maps and building geospatial datasets of the area. Two years later, we had produced geospatial datasets for the industrial history of the Lower River from 1858 to 1950, the changing course of the river and its historical tributaries over the same period, and nineteenth-century land ownership in the watershed. Project work resulted in the digitization of nearly 200 historic maps, many of which were later made available for free download to the public on the project website. [1] The website also incorporated a “points of interest” page, which links a GIS of historic sites throughout the watershed with archival images and narrative texts on the histories of those sites.

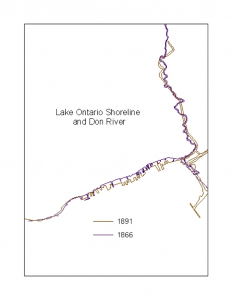

Placing the rich historical information from the Lower River into a GIS allowed me to create a spatial representation of a dynamic urban landscape, and compare changes in this landscape across time and space. Important aspects of the environmental history of the valley were now much more easily interpreted and illustrated: How did the nature of industry along the lower river change over time? What other kinds of land uses emerged? How did environmental and human-induced changes to the shape and alignment of the river channel and its terminal marsh manifest in the geographical record, and how did the spatial representation of these changes align with contemporary planning documents? The capacity of historical GIS to create layers of data for different periods was especially useful in interpreting these changes, facilitating as it did the detection of patterns and anomalies over time—something very difficult to achieve in the one-to-one comparison of print or even digital maps. Of course, our source material (historical maps of Toronto and its harbour, and fire insurance plans of the area surrounding the lower river) presented its own challenges and inconsistencies. I’ll talk about some of these challenges, and how we worked around them, in a subsequent post.

One of the things I became aware of as the project progressed, and which really allowed the project to happen in the first place, was the changing nature of libraries as institutions. As Marcel explains in a chapter we are co-authoring for an upcoming collection in NiCHE’s Canadian History & Environment series, university libraries perform a number of functions, some better known than others. They are places of study and research; physical collections; infrastructure to make these collections accessible (from bookshelves and map cabinets to sophisticated web portals); and lastly, they are providers of services, including reference and circulation services. Over the last twenty years, in response to the revolution in digital technology, and especially in specialized libraries like map and data libraries, these services have also come to mean teaching, in-depth research consultations, and even partnership in research. Increasingly, Marcel notes, library staff are being included in the research process because of their expertise with the subject matter, technical issues, and the material found in libraries.[2] The University of Toronto Map and Data Library is, at the moment, especially notable for its adoption of this new service model, but other university libraries (for example, map libraries at the University of Guelph, Trent University, and Dalhousie, among others) are moving in a similar direction.

Thus, not only are university map libraries fantastic repositories for historical data (in the form of paper maps) awaiting new life in digital format, they are also, increasingly, potential partners in historical research. As much as the Don Valley Historical Mapping Project benefitted my doctoral research, and saved me hours of frustrating and difficult comparisons of paper maps, it also benefitted the library by providing a rich and flexible resource for researchers from diverse disciplines, and an accessible resource for members of the general public. The project has been used by library staff to demonstrate the usefulness and the diversity of library services, and to broaden the appeal of the paper map collections. Long-time proponents of open and accessible data, libraries have an interest in supporting projects that showcase their collections in new ways, or that repurpose underused collections (such as paper maps) and place them in a more accessible format.

Looking back on the project, I’m aware of my good fortune in encountering such a receptive GIS and map librarian, in Marcel Fortin, and support from a network of academics in environmental history (NiCHE) that wanted to see such projects take root. I realized that despite the time and energy I invested to learn HGIS methods, I was unlikely to become proficient enough to do my own mapmaking accurately and efficiently—and at the very least, not gracefully. To echo Claire Campbell’s comment in response to Dan MacFarlane’s similarly-themed post, I’d rather sit on my couch and sip cappucino! Nevertheless, an understanding of how GIS works, and the particular challenges of historical GIS, proved extremely useful in working with the data, and members of the project team, effectively.

[1] Several maps still fall under copyright and cannot be made available as digital copy. Other maps were obtained through licensing which restrict their availability to the public.

[1] Several maps still fall under copyright and cannot be made available as digital copy. Other maps were obtained through licensing which restrict their availability to the public.

[2] Jennifer Bonnell and Marcel Fortin, DRAFT: “There’s Gold in those Drawers: The University of Toronto Map and Data Library and the Creation of the Don Valley Historical Mapping Project,” in Jennifer Bonnell and Marcel Fortin, eds., Historical GIS in Canada (under development for the University of Calgary Press and the Network in Canadian History and Environment).

Originally published for The Otter

Recent Comments